Supersonic Laminar Flow Control

aerospace

Supersonic Laminar Flow Control (LAR-TOPS-311)

Controls laminar flow over all major components of the airframe

Overview

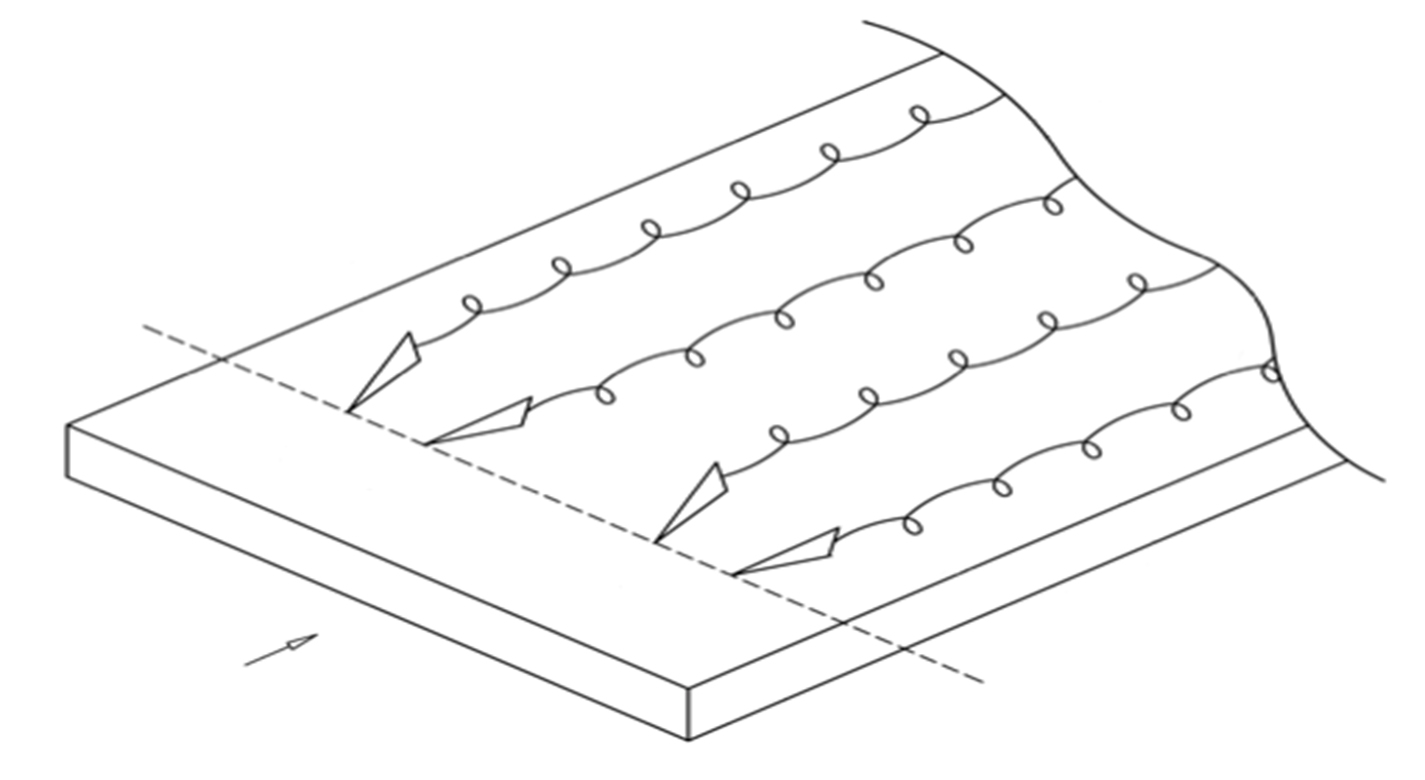

NASA's Langley Research Center has developed a technology that is projected to extend the laminar flow area over supersonic flight configurations by delaying the transition of boundary layer flow from laminar to turbulent state. This controls laminar flow over airframe components including wings, empennage, engine nacelles, and the nose region of an aircraft fuselage. It can be used in combination with many of the existing techniques for passive and active laminar flow control, but is particularly well-suited for a supersonic natural laminar flow design by virtue of avoiding the space, weight, system complexity, and maintenance penalties associated with suction based laminar flow control.

The Technology

This technique injects precisely defined stationary transient growth disturbances into the free air slipstream over a wing that develop into streamwise elongated "streaks." These streaks are created with an alternating pattern of low and high streamwise velocity in the boundary layer flow adjacent to the aerodynamic surface of interest. Judicious selection of streak wavelength, amplitude, and profile allows the first-mode instability waves responsible for transition via oblique mode breakdown to be damped while the remaining, uncontrolled waves are kept below an amplification threshold. A similar control concept is also applicable to second mode transition at hypersonic Mach numbers.

Benefits

- Potential to reduce skin friction drag up to 10-20%

- Can be used in combination with many of the existing techniques for passive and active laminar flow control

- Well-suited for a supersonic natural laminar flow design

- Applicable to multiple components of airframe

- Can be retrofit to current aircraft

Applications

- Commercial Supersonic aircraft

- UAVs

- Military strike aircraft

Similar Results

Low, Drag, Variable-Depth Acoustic Liner

The drag penalty incurred by a conventional acoustic liner is dependent, to a large extent, on the perforate open area ratio (porosity) of the perforated facesheet. As the open area ratio is decreased, the facesheet behaves more like a solid surface and the drag is reduced. However, if the open area ratio is too small, the external acoustic field will be isolated from the resonators (in the liner), and the system will not provide noise reduction.

The technology is a new type of variable-depth acoustic engine liner, which will reduce the drag and potentially manufacturing cost of this class of engine liner. Individual resonators within a conventional variable-depth liner are effective near resonance, but provide less acoustic benefit at other frequencies. In fact, at anti-resonance, a resonator behaves similar to a hard wall (i.e., the normal component of the particle velocity at the inlet is zero). Therefore, the proposed innovation couples neighboring resonators (tuned for different frequencies) together within the core of the liner. In other words, multiple resonators share a single inlet/port. Sharing inlets reduces the overall number of openings needed to maintain the acoustic performance of the liner by a factor of two or more. Reducing the open area ratio will in turn reduce the liner drag, and will reduce the number of holes that have to be machined into the facesheet, potentially reducing manufacturing cost.

The functional operation of the proposed innovation will be identical to conventional engine liners. The innovation enables a reduction of the open area ratio of the perforated facesheet (by a factor of two or more) without degrading the acoustic performance. This will decrease the liner drag, and has the potential to reduce the manufacturing cost of the liner, since fewer holes need to be machined in the facesheet.

Co-Optimization of Blunt Body Shapes for Moving Vehicles

Vehicles designed for purposes of exploration of the planets and other atmospheric bodies in the Solar System favor the use of mid-Lift/Drag blunt body geometries. Such shapes can be designed so as to yield favorable hypersonic aerothermodynamic properties for low heating and hypersonic aerodynamic properties for maneuverability and stability. The entry trajectory selected influences entry peak heating and integrated heating loads which in turn influences the design of the thermal protection system. A nominal is used to compare each shape considered. The vehicle will be subject to both launch and entry loading along with structural integrity constraints that may further influence shape design. Further, such vehicles must be sized so as to fit on existing or realizable launch vehicles, often within existing launch payload shroud constraints.

Improved Fixed-Wing Gust Load Alleviation Device

Gust loads may have detrimental impacts on flight including increased structural and aerodynamic loads, structural deformation, and decreased flight dynamic performance. This technology has been demonstrated to improve current gust load alleviation by use of a trailing-edge, free-floating surface control with a mass balance. Immediately upon impact, the inertial response of the mass balance shifts the center of gravity in front of the hinge line to develop an opposing aerodynamic force alleviating the load felt by the wing. This passive gust alleviation control covering 33% of the span of a cantilever wing was tested in NASA Langleys low speed wind tunnel and found to reduce wing response by 30%.

While ongoing experimental work with new laser sensing technologies is predicted to similarly reduce gust load, simplicity of design of the present invention may be advantageous for certification processes. Additionally, this passive technology may provide further gust alleviation upon extending the use of the control to the entire trailing edge of the wing or upon incorporation with current active gust alleviation systems.

Importantly, the technology can be easily incorporated into to the build of nearly all fixed wing aircrafts and pilot control can be maintained through a secondary trim tab. Though challenging to retrofit, passive gust alleviation could enable use of thinner, more efficient wings in new plane design.

Multistage Free-Flight Testing System

The disclosed technology provides a multistage system for evaluating the free-flight behavior of test articles across of the supersonic, transonic, and subsonic regimes. First, a drop platform is lifted to high altitudes using a lifting device, such as a stratospheric balloon. The drop platform houses multiple projectiles, each containing an ejection mechanism, an on-board avionics suit, and an instrumented test article. Upon reaching the target altitude via the lifting device, the drop platform releases the projectiles sequentially. Each projectile accelerates to a target speed and altitude before ejecting its test article into the freestream. The test articles, such as a scaled re-entry capsule, then collect flight data during their descent through the various Mach regimes, providing valuable insights into their flight performance under mission-relevant conditions.

This innovative testing system offers several benefits. It enables the simultaneous testing of multiple vehicles, facilitating the evaluation of design variations as well as statistical analyses of vehicle behavior. This system also provides significant cost savings in comparison to other state-of-the-art testing methods, such as ballistic range testing. Additionally, the test articles within each projectile are easily interchangeable through a simple, modular change of a support surface in the ejection mechanism. This flexibility enables the system to accommodate a range of other aerodynamic technologies, including other vehicles, parachutes, propulsion systems, and defense technologies. This system can enhance the efficiency and robustness of reentry vehicle design, testing, and simulation operations through the collection of rich, flight-relevant data.

Aerospace Vehicle Entry Flightpath Control

This novel flightpath control system exploits the dihedral effect to control the bank angle of the vehicle by modulating sideslip (Figure 1). Exploiting the dihedral effect, in combination with significant aerodynamic forces, enables faster bank accelerations than could be practically achieved through typical control strategies, enhancing vehicle maneuverability. This approach enables vehicle designs with fewer control actuators since roll-specific actuators are not required to regulate bank angle. The proposed control method has been studied with three actuator systems (figure below), Flaps Control System (FCS); Mass Movement Control System (MMCS); and Reaction Control System (RCS).

• FCS consists of a flap configuration with longitudinal flaps for independent pitch control, and lateral flaps generating yaw moments. The flaps are mounted to the shoulder of the vehicle’s deployable rib structure. Additionally, the flaps are commanded and controlled to rotate into or out of the flow. This creates changes in the vehicle’s aerodynamics to maneuver the vehicle without the use of thrusters.

• MMCS consists of moveable masses that are mounted to several ribs of the DEV heatshield, steering the vehicle by shifting the vehicle’s Center of Mass (CoM). Shifting the vehicle’s CoM adjusts the moment arms of the forces on the vehicle and changes the pitch and yaw moments to control the vehicle’s flightpath.

• RCS thrusters are mounted to four ribs of the open-back DEV heatshield structure to provide efficient bank angle control of the vehicle by changing the vehicle’s roll. Combining rib-mounted RCS thrusters with a Deployable Entry Vehicle (DEV) is expected to provide greater downmass capability than a rigid capsule sized for the same launch