Search

Electrical and Electronics

Passive PCB-Mounted Thermal Switch

NASA’s Passive PCB-Mounted Thermal Switch uses a heat pipe that extends from the electronics enclosure wall to the center of the electronics board. The switch includes a wax actuator that extends when warm. The extending piston on the actuator pushes the heat pipe against the anvil of the mechanism, which then provides a low-resistance heat path to the wall of the enclosure. When the wax actuator drops below a certain temperature, the piston retracts. A spring then pushes the heat pipe away from the anvil, breaking thermal contact and conserving heat. A series of insulating materials is used to reduce unwanted heat transfer through the springs. The mechanism is mounted to the board with a thermal interface material and screws to provide high contact pressure and thermal conductivity between the board and the mechanism. Additional heat straps are used to carry heat directly from particularly hot components.

A key advantage of this NASA invention is that it does not require any energy input for operations (i.e., it is completely passive). In spaceflight applications, this enables significant mass savings as heaters can represent up to 50% of electronics systems’ power consumption. Given that typical battery chemistries stop functioning at approximately 0C, additional power is required to keep the batteries themselves warm. Thus, reducing heater power requirements by 50% could reduce overall energy storage requirements by approximately 70% – leaving more capacity for sensors, fuel, or other priorities.

NASA’s switch is particularly useful for spaceflight applications where electronics are exposed to long bouts of extreme heat and cold, such as on the Moon (where the day-night cycle lasts 14 days with nighttime lows near -173C and daytime highs near 127C), or in deep space. Lunar landers and lunar infrastructure developers might be ideal end-users of the invention. Other applications where electronics experience extreme temperatures may benefit from this NASA innovation.

Materials and Coatings

New Methods in Preparing and Purifying Nanomaterials

Sometimes called white graphite, affordable and plentiful hBN possesses the same kind of layered molecular structure as graphite. In graphite, this structure has allowed next-generation nanomaterials like carbon nanotubes and graphene to be produced. With hBN, however, the process of converting the substance into boron nitride nanotubes (BNNT) has been too difficult to yield commercial quantities. Glenn innovators have created several new methods that could enable greater adoption of this unique nanomaterial. In the initial stage, the starter reactant is mixed with a selected set of chemicals (a metal chloride, for example) and an activation agent (such as sodium fluoride). This mixture causes hBN to become less resistant to intercalation. The intercalated product can then be exfoliated by heating the material in air, and giving the material a final rinse with a liquid-phase ferric chloride salt to dissolve any embedded impurities without damaging its internal structure. These efficiently exfoliated nanomaterials can be used to form advanced composite materials (e.g., layered with aluminum oxide to form hBN/alumina ceramic composites). Nanomaterials fabricated from hBN can also take advantage of the material's unique combination of being an electrical insulator with high thermal conductivity for applications ranging from microelectronics to energy harvesting. Glenn's innovations have enabled a significantly improved matrix composite material with the potential to make a significant impact on the commercial materials market.

Power Generation and Storage

Next Generation Li-Ion Calorimeter

Among the enhancements reflected in the Next Generation Li-ion Calorimeter is a rigidly wired system that allows direct mounting of thermocouples into key component locations to better capture thermal signature data during testing and improve thermocouple reliability. The ejecta mating chambers have also been modified for better thermal containment and easier system disassembly. Additionally, the system facilitates an easier access, user-friendly Destructive Physical Analysis (DPA) process between uses, and reflects durability improvements in the face of repetitive heat cycling.

A clean-sheet redesign was undertaken to create a configurable insula-tion case with an interchangeable “window” section, tailored to the ex-perimental environment. For NASA’s Energy Systems Test Area (ESTA) evaluation, a window with the original foam is installed to maintain ther-mal insulation performance. In contrast, for synchrotron experiments, this section is replaced with an aluminum window that eliminates foam-related X-ray scattering. This modification has substantially improved X-ray radiography resolution, enabling clearer imaging of fine internal battery features during thermal runaway events. Moreover, the insulation case was designed to provide system fire-proofing for both the chamber and pouch cell testing case configurations.

Lastly, a control switchbox is also being developed to work with the latest generation calorimeter. It allows users to remotely operate the TR trigger mechanism from a control room, automatically terminate power in a prescribed amount of time to prevent a fire caused by overheating, and provides lit indicators to inform the user of ready or fault states.

manufacturing

Woven Thermal Protection System

Going farther, faster and hotter in space means innovating how NASA constructs the materials used for heat shields. For HEEET, this results in the use of dual-layer, three-dimensional, woven materials capable of reducing entry loads and lowering the mass of heat shields by up to 40%. The outer layer, exposed to a harsh environment during atmospheric entry, consists of a fine, dense weave using carbon yarns. The inner layer is a low-density, thermally insulating weave consisting of a special yarn that blends together carbon and flame-resistant phenolic materials. Heat shield designers can adjust the thickness of the inner layer to keep temperatures low enough to protect against the extreme heat of entering an atmosphere, allowing the heat shield to be bonded onto the structure of the spacecraft itself. The outer and inner layers are woven together in three dimensions, mechanically interlocking them so they cannot come apart. To create this material, manufacturers employ a 3-D weaving process that is similar to that used to weave a 2-D cloth or a rug. For HEEET, computer-controlled looms precisely place the yarns to make this kind of complex three-dimensional weave possible. The materials are woven into flat panels that are formed to fit the shape of the capsule forebody. Then the panels are infused with a low-density version of phenolic material that holds the yarns together and fills the space between them in the weave, resulting in a sturdy final structure. As the size of each finished piece of HEEET material is limited by the size of the loom used to weave the material, the HEEET heat shield is made out of a series of tiles. At the points where each tile connects, the gaps are filled through inventive designs to bond the tiles together.

Mechanical and Fluid Systems

Passive Fuel Cell Surface Power System (PaCeSS)

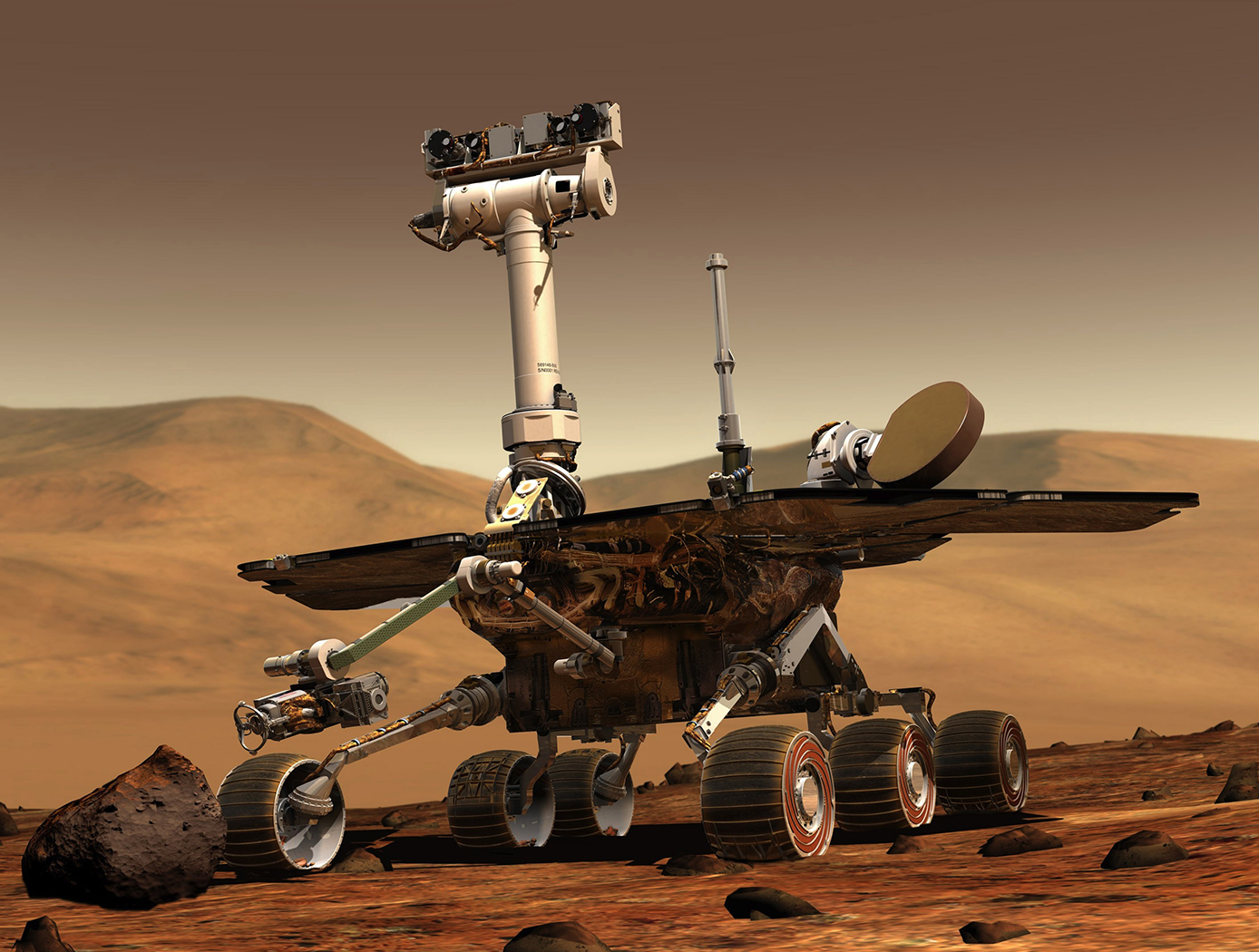

NASA’s envisioned Lunar and Martian surface operations will require constant and reliable power systems. Traditional power architectures, including solar cells and batteries, cannot be solely relied upon due to the lengthy lunar nights and challenging thermal environments. How-ever, fuel cells, including primary fuel cells and regenerative fuel cells, represent a promising means for energy generation and storage on planetary and lunar surfaces.

PaCeSS could further improve mission flexibility by significantly enhanc-ing reliability and longevity with fully passive fuel cell power generation capability. Test systems have been built to validate the performance characteristics of various PaCeSS technology elements, and many of the component materials have already been characterized. Some of these novel technology elements already demonstrated include a two-phase thermosyphon operation in fuel cell conditions, a passive shape memory actuator operation using two-phase water, and a shape memory alloy radiator turndown.

Although the current design of the shape memory alloy actuated rad-iator system is dependent on partial gravity and space-like environments where heat rejection is performed primarily via radiation, there may be ways of using the same basic system for controlling fuel cell temper-ature via convective heat rejection for terrestrial applications. Addition-ally, other elements of this concept could be commercialized terrestri-ally, including the thermosyphon heat transport mechanism, a multi-purpose vapor chamber, and a thermal management system that uses water by-product as the thermal management medium.

The Passive Fuel Cell Surface Power System is at a technology readiness level (TRL) 3 (analytical and experimental critical function and/or characteristic proof of concept) and is now available for patent licensing. Please note that NASA does not manufacture products itself for commercial sale.