Tension Element Damping (TED) – With Hydraulics for Large Displacements

Mechanical and Fluid Systems

Tension Element Damping (TED) – With Hydraulics for Large Displacements (MFS-TOPS-109)

Disruptive modal coupling damps large structure vibrations using small footprint devices

Overview

NASA engineers developed a new approach to mitigating unwanted structural vibrations that cause maintenance issues and compromise the performance and safety of large, tall structures. NASAs method is fundamentally different from conventional passive and active vibration damping methods used today. TED uses disruptive modal coupling between two different structures, each with their own vibrational behavior, to provide vibration damping for one or both of the structures. This novel reactive vibration damping method uses feedback from the vibrational displacement itself, such as the tension and compression cycles from the movement of the vibrating structure (like a wind turbine or tower), to disrupt the vibration. Line tension is provided by either hydraulic, pneumatic, or magnetic means to suit the application and the size/ displacement of the vibration. Compared to conventional spring dampers, TED devices are simple in design, lightweight, very effective, and have a smaller footprint.

The Technology

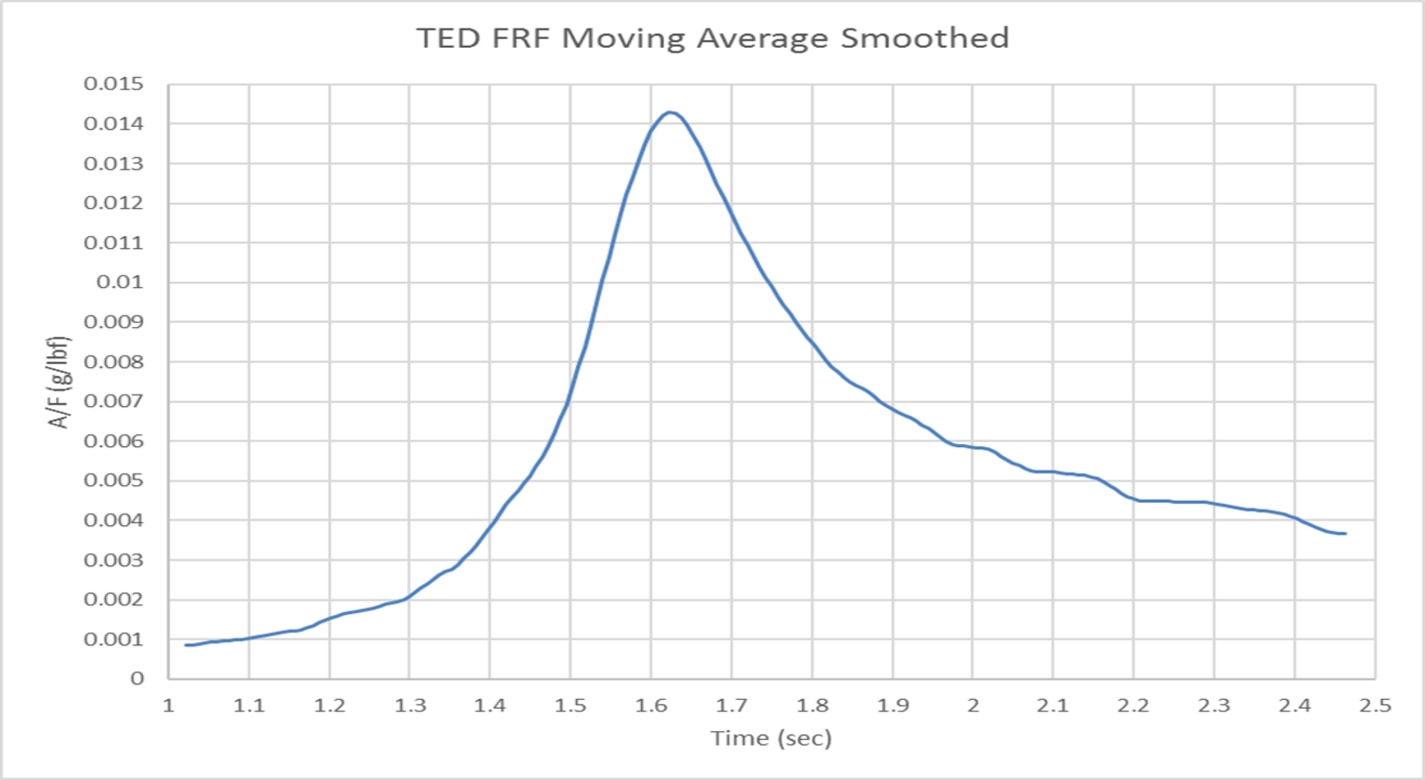

The Rotational Tension Element Damper (RTED) uses a controlled tension line, backed by hydraulics, to damp large displacements in large structures. NASA built RTED prototypes that have been successfully tested on a 170-foot long wind turbine blade in test beds at the University of Maine. In this case, the RTED device damps the vibration of the large, tall turbine blades relative to a stationary anchor structure on the ground using a line and spring coupled to both the blade and the anchor, and controlled by a spool fitted with a one-way clutch. When force is applied, from heavy wind for example, the resulting movement of the tall structure triggers the necessary tension and compression cycles in the system to engage the rotating damper. The reaction force interferes with the rotation speed of the spool and disrupts and damps the vibration in the tall structure. The figure below shows test data for the RTED used on the wind turbine.

Benefits

- Spatially efficient: damps vibration in large structures with a smaller footprint than previous damping methods

- Adaptable: responds to changing vibration amplitudes

- Effective: may increase wind turbine reliability

- Adjustable: damping can be tuned in two dimensions

- Reliable: Unlike conventional springs and dampers, reactive damping will not impose rogue loads

Applications

- Wind turbines

- Solar arrays

- Liquid nitrogen gas (LNG) platforms

- Commercial space mobile launchers

- Towers

- Industrial process stacks and equipment

|

Tags:

|

|

|

Related Links:

|

Similar Results

Tension Element Vibration Damping

NASAs Tension Element Vibration Damping technology presents a novel method of managing the dynamic behavior of structures by capturing the vibrational displacement of the structure via a connecting link and using this motion to drive a resistive element. The resistive element then provides a force feedback that manages the dynamic behavior of the total system or structure. The damping force feedback can be a tensile or compressive force, or both. Purely tensile force has advantages for packaging and connection alignment flexibility while combined tensile/compression forces have the advantage of providing damping over a complete vibratory cycle.

This innovation can be readily applied to existing structures and incorporated into any given design as the connecting element is easily affixed to displacing points within the structure and the resistive element to be located in available space or a convenient location. The resistive element can be supplied by any one of either hydraulic, pneumatic or magnetic forces. As such the innovation can provide a wide range of damping forces, a linear damping function and/or an extended dynamic range of attenuation, providing broad flexibility in configuration size and functional applicability.

NASA-built prototypes have been shown to be highly effective on a 170-foot long wind turbine blade in test beds at the University of Maine.

Self-Tuning Compact Vibration Damper

Structural vibrations frequently need to be damped to prevent damage to a structure or payload. To accomplish this, a standard linear damper or elastomeric-suspended masses are used. The problem associated with a linear damper is the space required for its construction. For example, if the damper's piston is capable of three inches of movement in either direction, the connecting shaft and cylinder each need to be six inches long. Assuming infinitesimally thin walls, connections, and piston head, the linear damper is at least 12 inches long to achieve +/3 inches of movement. Typical components require 18+ inches of linear space. Further, tuning this type of damper typically involves fluid changes, which can be tedious and messy. Masses suspended by elastomeric connections enable even less range of motion than linear dampers.

The NASA invention is a compact and self-tunable structural vibration damper. The damper includes a rigid base with a slider mass for linear movement. Springs coupled to the mass compress in response to the linear movement along either of two opposing directions. A rack-and-pinion gear coupled to the mass converts the linear movement to a corresponding rotational movement. A rotary damper coupled to the converter damps the rotational movement. To achieve +/- 3 inches of movement, this design requires slightly more than six inches of space.

Compact Vibration Damper

Structural vibrations frequently need to be damped to prevent damage to a structure. To accomplish this, a standard linear damper or elastomeric-suspended masses are used. The problem associated with a linear damper is the space required for its construction. For example, if the damper's piston is capable of three inches of movement in either direction, the connecting shaft and cylinder each need to be six inches long. Assuming infinitesimally thin walls, connections, and piston head, the linear damper is at least 12 inches long to achieve +/-3 inches of movement. Typical components require 18+ inches of linear space. Further, tuning this type of damper typically involves fluid changes, which can be tedious and messy. Masses suspended by elastomeric connections enable even less range of motion than linear dampers.

The NASA invention is for a compact and easily tunable structural vibration damper. The damper includes a rigid base with a slider mass for linear movement. Springs coupled to the mass compress in response to the linear movement along either of two opposing directions. A rack-and-pinion gear coupled to the mass converts the linear movement to a corresponding rotational movement. A rotary damper coupled to the converter damps the rotational movement. To achieve +/- 3 inches of movement, this design requires slightly more than six inches of space.

.jpg)

Fluid-Filled Frequency-Tunable Mass Damper

NASA MSFC’s Fluid-Filled Frequency-Tunable Mass Damper (FTMD) technology implements a fluid-based mitigation system where the working mass is all or a portion of the fluid mass that is contained within the geometric configuration of either a channel, pipe, tube, duct and/or similar type structure. A compressible mechanism attached at one end of the geometric configuration structure enables minor adjustments that can produce large effects on the frequency and/or response attributes of the mitigation system.

Existing fluid-based technologies like Tuned Liquid Dampers (TLD) and Tuned Liquid Column Dampers (TLCD) rely upon the geometry of a container to establish mitigation frequency and internal fluid loss mechanisms to set the fundamental mitigation attributes. The FTMD offers an innovative replacement since the frequency of mitigation and mitigation attributes are established by the compressible mechanism at the end of the container. This allows for simple alterations of the compressible mechanism to make frequency adjustments with relative ease and quickness.

FTMDs were recently successfully installed on a building in Brooklyn, NYC as a replacement for a metallic TMD, and on a semi-submersible marine-based wind turbine in Maine.

The FTMD technology is available for non-exclusive licensing and partially-exclusive licensing (outside of building construction over 300 feet).

Fluid Structure Coupling Technology

FSC is a passive technology that can operate in different modes to control vibration:

Harmonic absorber mode: The fluid can be leveraged to act like a classic harmonic absorber to control low-frequency vibrations. This mode leverages already existing system mass to decouple a structural resonance from a discrete frequency forcing function or to provide a highly damped dead zone for responses across a frequency range.

Shell mode: The FSC device can couple itself into the shell mode and act as an additional spring in a series, making the entire system appear dynamically softer and reducing the frequency of the shell mode. This ability to control the mode without having to make changes to the primary structure enables the primary structure to retain its load-carrying capability.

Tuned mass damper mode: A small modification to a geometric feature allows the device to act like an optimized, classic tuned mass damper.