Active Turbulence Suppression System for Electric Vertical Take-Off and Landing (eVTOL) vehicles

Aerospace

Active Turbulence Suppression System for Electric Vertical Take-Off and Landing (eVTOL) vehicles (TOP2-308)

Suppression of Dutch-Roll Oscillations for Air Taxis Using Existing Propellers

Overview

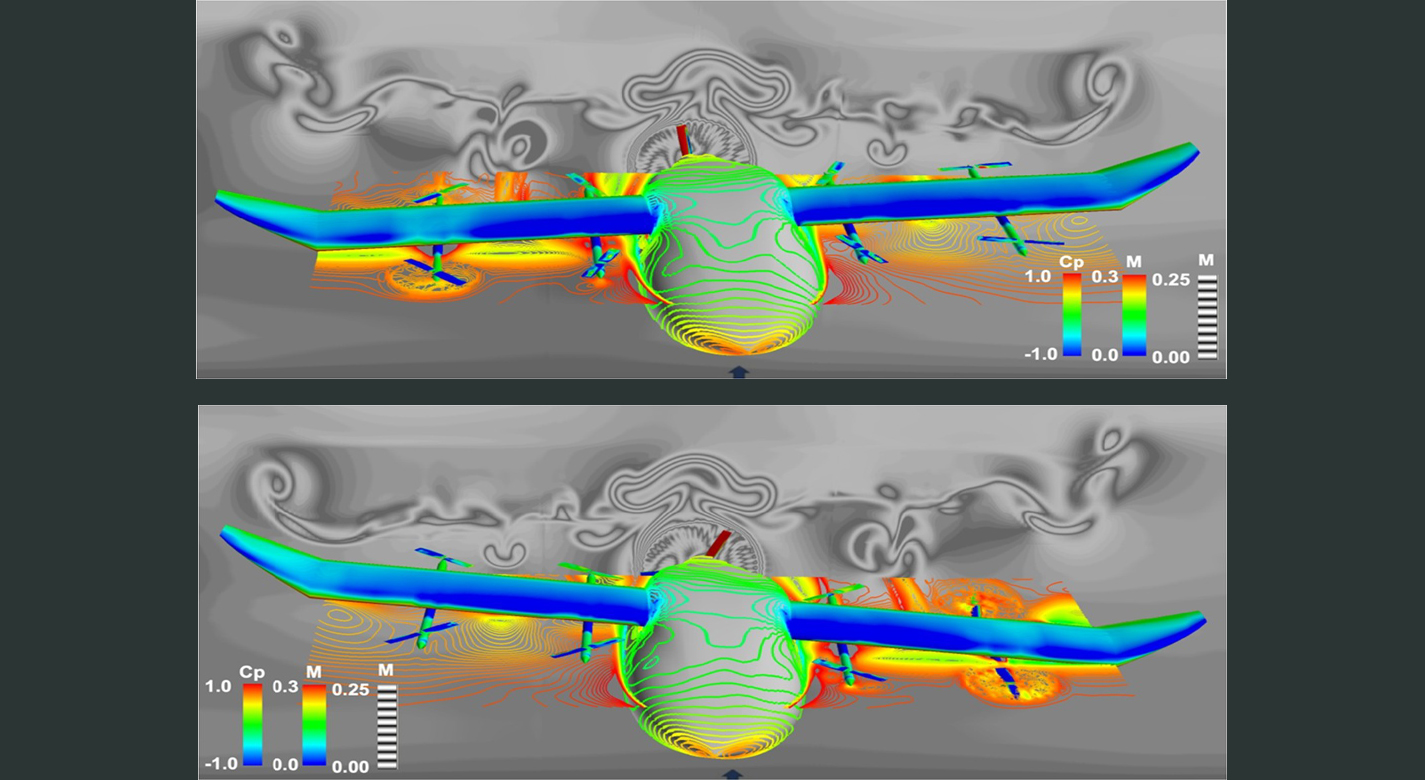

Electric Vertical Take-Off and Landing (eVTOL) aircraft, conceptualized to be used as air taxis for transporting cargo or passengers, are generally lighter in weight than jet-fueled aircraft, and fly at lower altitudes than commercial aircraft. These differences render them more susceptible to turbulence, leading to the possibility of instabilities such as Dutch-roll oscillations. In traditional fixed-wing aircraft, active mechanisms used to suppress oscillations include control surfaces such as flaps, ailerons, tabs, and rudders, but eVTOL aircraft do not have the control surfaces necessary for suppressing Dutch-roll oscillations. NASA Ames has developed a novel approach for actively controlling Dutch-roll oscillations of an eVTOL aircraft by using existing outboard propellers to dampen oscillations. This novel technology avoids the need to add hardware or change the design of eVTOL vehicles to address the negative effects of turbulence.

The Technology

The Active Turbulence Suppression (ATS) system for electric Vertical Take-Off and Landing (eVTOL) vehicles employ existing lifting propellers to dampen instabilities during flight, such as Dutch-roll oscillations and other gust-induced oscillations. When a roll angle of an eVTOL aircraft has deviated or is about to deviate from a current stable aircraft state to an undesirable, unstable, and oscillating aircraft state, the ATS system queries a turbulence suppression database that stores a set of propeller speed profiles for mitigation a deviation of a given roll angle for a particular aircraft with specified propellers. Using this data, the eVTOL flight controller adjusts the speed of the propellers for a certain duration of time, according to the propeller speed profiles for mitigating the deviation. In models of aircraft with adjustable propeller angles, the database includes blade angle profiles for mitigating the effects of turbulent conditions. Timing and rate of propeller activation can be pre-computed using higher order computational modeling performed with NASA’s super computing resources. Because the data is pre-computed, the use of the ATS system onboard does not require significant computing resources to implement on eVTOL vehicles. The technology, a mechanism by which existing eVTOL propellers are leveraged to suppress gust-induced oscillations enables a safe and comfortable passenger experience at low-cost and without added hardware.

Benefits

- Enables a safe and comfortable passenger experience: solves gust-induced oscillation instabilities for eVTOL aircraft, which experience challenges due to their relatively light weight

- Compatible with most eVTOL designs with multiple propellers

- Does not require additional hardware: eVTOL manufacturers benefit from ability to keep aircraft weight low, enabling longer battery life and thus vehicle range

- Low cost to implement: design costs can be significantly reduced with high fidelity modeling of flows by using the Navier Stokes equations and reducing amount of wind tunnel test cases

Applications

- electric Vertical Take-Off and Landing (eVTOL) industry

- Air- Taxis industry

- Aerospace industry

- eVTOL manufacturers

Technology Details

Aerospace

TOP2-308

ARC-18707-1

https://www.sciencedirect.com/science/article/pii/S1270963821006684

https://arc.aiaa.org/doi/10.2514/1.J060055

https://www.nas.nasa.gov/SC21/research/project1.html#demo-2

https://arc.aiaa.org/doi/10.2514/3.10179

|

Tags:

|

|

|

Related Links:

|

Similar Results

Fixed Wing Angle eVTOL

While previous eVTOLs often require a near 90° wing tilt to position propellers in an optimal location to generate vertical force for takeoff, NASA has taken a very different approach. NASA's design instead uses a slight wing angle and large flaps designed to deflect slipstream generated by the propellers to create a net positive force in the vertical direction, all while preventing forward movement. This unique configuration allows for takeoff and landing operations without the need for near 90° wing tilt angles. After takeoff, the transition to forward flight only requires a slight change in attitude of the vehicle and retraction of the flaps. Similar solutions require large changes in attitude to accomplish this transition which is often undesirable, especially for air taxi operations that involve passengers.

Given the effectiveness of this configuration for generating upward force, the requirement for wing angle tilt has been reduced from near 90° to approximately 15° during takeoff. Further iterations may reduce this requirement even further to 0°. By eliminating the need for near 90° wing tilt, NASA's eVTOL design removes the need for mechanisms to perform active tilting of the wings or rotors, reducing system mass and thereby improving performance. Flaps represent the only components that require actuation for takeoff and landing operations.

Innovators at NASA leveraged the Langley Aerodrome 8 (LA-8), a modular testbed vehicle that allows for rapid prototyping and testing of eVTOLs with various configurations, to design and test this novel concept.

Aerodynamic Framework for Parachute Deployment from Aerial Vehicle

For rapid parachute deployment simulation, the framework and methodology provided by the simulation database uses parametrized aerodynamic data for a variety of environmental conditions, air taxi design parameters, and landing system designs. The database also includes a compilation of drag coefficients, thrust and lift forces, and further relevant aerodynamic parameters utilized in the simulated flight of a proposed air taxi. The database and framework can be constructed using simulated data that accounts for oscillatory breathing of parachutes. The methodology can further employ an overset grid of body-fitted meshes to accurately capture deployment of an internally-stored parachute, as well as descent of the air taxi and deployed parachute.

The systems and methods of the disclosed technology can be utilized with existing CFD solvers in a plug-and-play manner, such that the framework can be integrated to directly improve the performance of these solvers and the machines on which they are installed. The framework itself can employ parallelization to enable distributed solution of intensive CFD simulations to build a robust database of simulated data. Further, as up to 90% of computational time is spent in the calculation of aerodynamic parameters for use in coupled trajectory equations, the framework can significantly reduce the computational costs and design time for safe landing systems for air taxis. These reductions can lead to lower costs for design processes, while enabling rapid design and testing prior to physical prototyping.

Rapid Aero Modeling for Computational Experiments

RAM-C interfaces with computational software to provide test logic and manage a unique process that implements three main bodies of theory: (a) aircraft system identification (SID), (b) design of experiment (DOE), and (c) CFD. SID defines any number of alternative estimation methods that can be used effectively under the RAM-C process (e.g., machine learning techniques, regression, neural nets, fuzzy modeling, etc.). DOE provides a statistically rigorous, sequential approach that defines the test points required for a given model complexity. Typical DOE test points are optimized to reduce either estimation error or prediction error. CFD provides a large range of fidelity for estimating aircraft aerodynamic responses. In initial implementations, NASA researchers “wrapped” RAM-C around OVERFLOW, a NASA-developed high-fidelity CFD flow solver. Alternative computational software requiring less time and computational resources could be also utilized.

RAM-C generates reduced-order aerodynamic models of aircraft. The software process begins with the user entering a desired level of fidelity and a test configuration defined in terms appropriate for the computational code in use. One can think of the computational code (e.g., high-fidelity CFD flow solver) as the “test facility” with which RAM-C communicates with to guide the modeling process. RAM-C logic determines where data needs to be collected, when the mathematical model structure needs to increase in order, and when the models satisfy the desired level of fidelity.

RAM-C is an efficient, statistically rigorous, automated testing process that only collects data required to identify models that achieve user-defined levels of fidelity – streamlining the modeling process and saving computational resources and time. At NASA, the same Rapid Aero Modeling (RAM) concept has also been applied to other “test facilities” (e.g., wind tunnel test facilities in lieu of CFD software).

Aerodynamically Actuated Thrust Vectoring Device

The thrust actuating device includes several innovations in the aerodynamically stable tilt actuation of propellers, propeller pylons, jets, wings, and fuselages, collectively called propulsors. The propulsors rotate between hover and forward flight mode for a tilt-wing or tilt-rotor aircraft. A vehicle designed using this technology can transition from a hovering flight condition to a wing born flight condition with no mechanical actuation and can do so without complex control systems. This results in a reduction in system weight and complexity and produces a robust and naturally stable hovering aircraft with efficient forward flight modes.

Wind-Optimal Cruise Airspeed Mode for Flight Management Systems (FMS)

The novel approach for optimizing airspeed for both actual and predicted wind conditions in electric Vertical Takeoff and Landing (eVTOL) aircraft with Distributed Electric Propulsion (DEP) systems includes the process of creating a lookup table for wind‐optimal airspeed as a function of wind magnitude, considering the direction of the wind relative to the cruise segment, considering the cruise altitude for an aircraft type, and incorporating the wind-optimal airspeed lookup table in the performance database for real‐time access by the Flight Management Systems (FMS) to predict wind-optimal airspeed at waypoints of the flight plan. The target wind‐optimal airspeed is updated in real-time throughout the cruise portion of a flight.

In a test of the wind-optimal airspeed targeting technique using a multi-rotor aircraft model, results obtained show benefits of flying at the wind‐optimal cruise airspeed compared to the best‐range airspeed. In headwind conditions, energy consumption was reduced by up to 7.5%, and flight duration was reduced by up to 28%. Under uncertain wind magnitudes, flying at wind-optimal airspeed offered lower variability and higher predictability in energy consumption than flying at best‐range airspeed.