Origami-based Deployable Fiber Reinforced Composites

materials and coatings

Origami-based Deployable Fiber Reinforced Composites (LAR-TOPS-372)

Using the shape memory effect to deploy structural composite materials

Overview

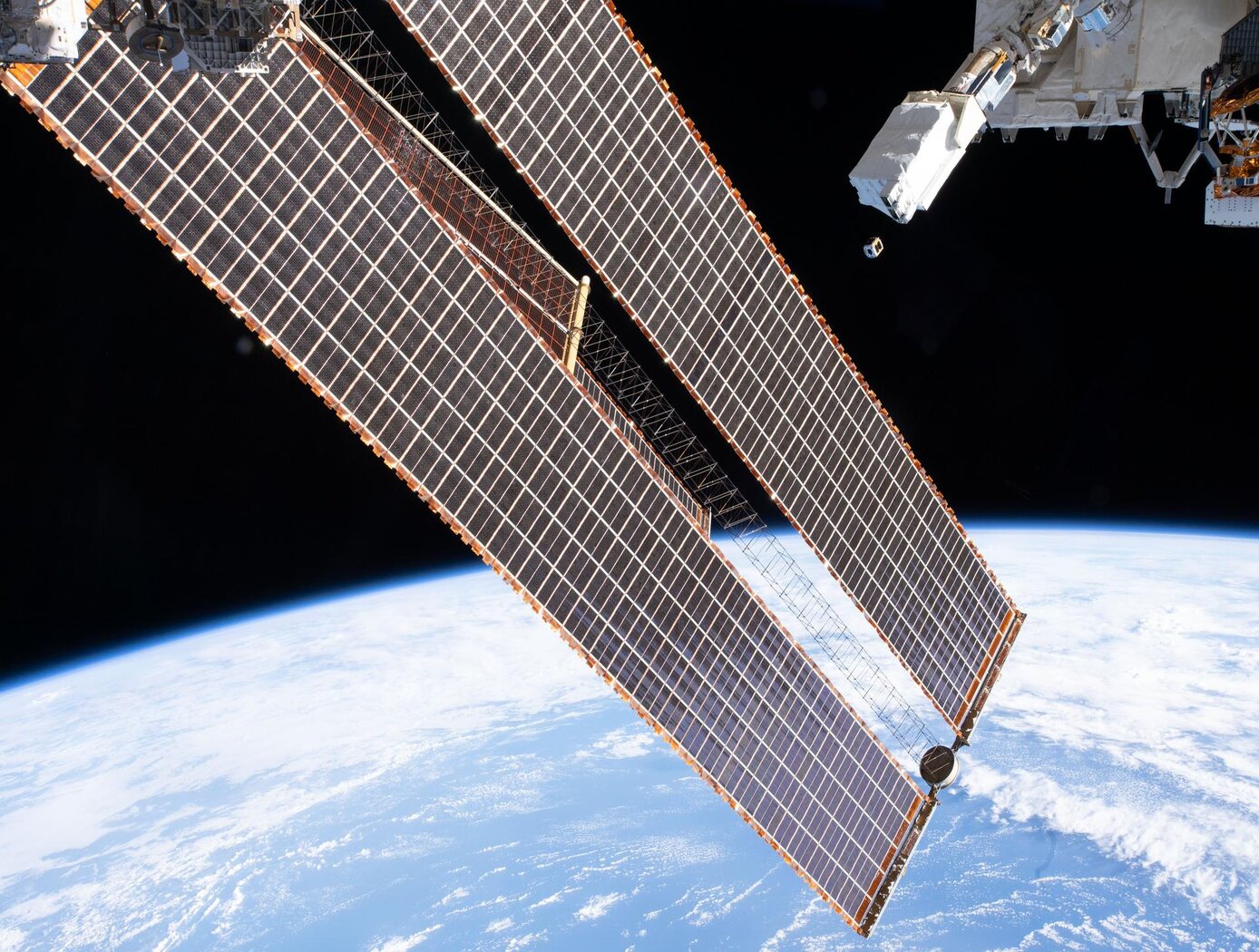

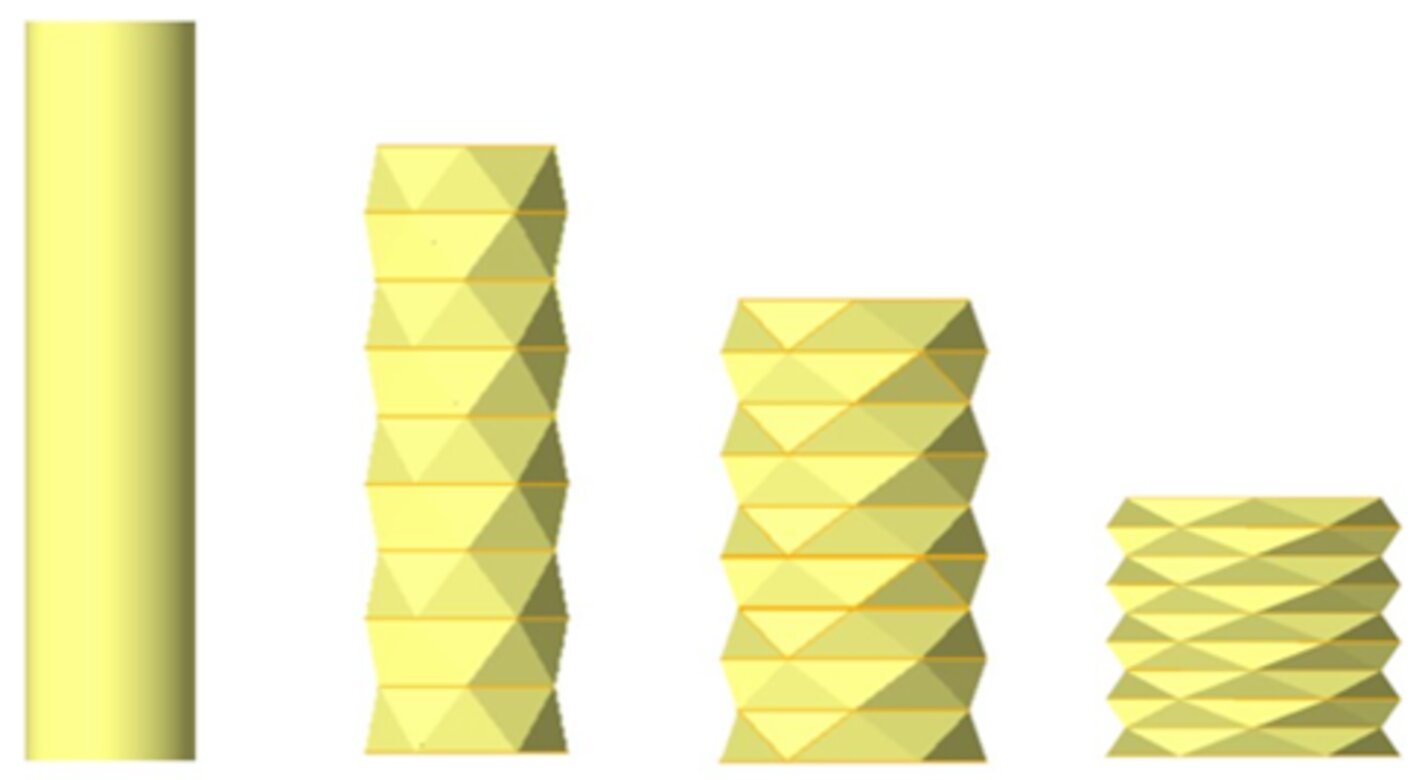

Inventors at the NASA Langley Research Center have developed a new UV (ultraviolet)-curable polymer carbon fiber composite and the origami-based deployable structures that are made from the new composite. The new composite and associated origami deployment system were developed for use in stronger, more reliable deployable space structures. These structures include beams for deployable habitats, booms, solar array frames, and antenna supports among others. The polymer shape memory effect allows the origami composite structures to be stored in a small, lightweight package and deployed on-site (i.e., in orbit, on the moon, etc.) through heating. The origami-based composite assemblies outperform other composite-based deployable structures in strength, are lighter than metals, are not susceptible to gas leaks like inflatable structures, and do not require motors to deploy.

The Technology

Deployable space structures often rely upon telescoping or folding structures that either must be manually deployed or deployed by attached motors. These structures are often made from heavier (relative to carbon fiber composites) metals to provide enough strength to support a load. As such, there is a need for in-space structures that are lightweight, can be packaged compactly, and can be deployed easily.

The composite material developed here does not require high temperature baking to cure the polymer, rather relying on UV light to solidify the polymer component. The composite is then included into origami-based structures that can fold and deploy using the polymer shape memory effect. The composite is first trained to assume the deployed structural shape when heated; it is then folded like origami and frozen into the packaged shape for storage and launch. Combining the composite material with the origami-inspired design leads to high strength structures (can hold at least 600 kg on Earth). To date, a ~5-inch prototype structural bar has been produced using the UV-curable composite and further development is on-going at NASA Langley.

The deployable origami composite structures are at technology readiness level (TRL) 4 (component and/or breadboard validation in laboratory environment) and are available for patent licensing.

Benefits

- Not prone to failure: telescoping, motor driven, and inflatable structures have failure potential from parts not working or gas leaks.

- High strength when deployed: demonstrated to have at least a 600 kg load capacity under Earth gravity.

- Simple, automatic deployment mechanism: the origami-inspired folding mechanism only requires heat to deploy, no manual intervention.

- Small stowage volume: the composites can be folded and packaged into a small volume for launch.

- Lightweight: carbon fiber polymer composites are lighter weight than typically used metals.

Applications

- In-space uses: replacing metal support structures like booms, habitat beams, solar array frames, antennae supports, solar sail supports, etc.

- Military: deployable habitats and mobile barracks.

- Consumer goods: tents, camping equipment, etc.

Technology Details

materials and coatings

LAR-TOPS-372

LAR-20197-1

Origami-based Composite Space Structures, Rebecca Hall, Jin Ho Kang, Keith L Gordon, Sheila Thibeault, and Jeff Hinkley, 2021 Fall Student Research Symposium, December 15, 2021, https://ntrs.nasa.gov/api/citations/20210025400/downloads/Rebecca%20Hall%202021%20FALL%20NIFS-Presentation.pdf

Similar Results

Low Creep, Low Relaxation Fiber-Reinforced Polymer Composites

NASA used three strategies to develop a family of modified epoxy resins for use in an improved composite layup configuration. By tailoring molecular structures, incorporating secondary additives, and adjusting composite architecture, NASA has produced fiber-reinforced polymer composites that suppress viscoelastic creep and relaxation. Specifically the three strategies were:

(1) Controlling the cross-linking density using reactive functional groups and selecting appropriate monomers with stoichiometry adjustments. A higher stoichiometric ratio is responsible for reduced relaxation compared to a lower ratio (resulting in 26% relaxation after 1 year vs. 49%).

(2) Increase the steric hindrance by reducing free volume and enhancing intermolecular interaction. This involved the preparation of two different reactive low molecular weight oligomers The best epoxy resin created was from the VCD/HAA additives with 15-17% relaxation; DEGBA/HAA had 22-25% relaxation.

(3) Optimizing different carbon fiber layup configurations for woven structures made into a highly stiff boom, highly flexible boom, a small size boom, and a large size boom application. The best configuration was that of a highly stiff boom with 4-5% relaxation. Other carbon fiber layup configurations had 16-30% relaxation.

As shown in the figure below, NASA tested the relaxed composite using an accelerated test with variable temperatures.

Vertically Aligned Carbon Nanotubes

Formation of the inventive polymer composite matrix begins by growing carbon nanotubes directly on a veil substrate. The carbon nanotubes are grown from both sides of a non woven carbon fiber mat. The carbon nanotubes can be single or multi walled and can be grown to predetermined lengths. The veiled substrate is positioned between carbon fiber/ polymer prepreg layers such that the carbon nanotubes protrude into the reinforcement layers. The polymer composite matrix formed following curing of the resin exhibits improved interlaminar strength, fracture toughness and impact resistance. Because of the thinness of the veil layer, electricity can pass from conductive carbon nanotubes on one side of the veil to conductive carbon nanotubes on the other side of the veil. Electricity can also pass between two veils intercalated into the same reinforcement layer when the length of the nanotubes is sufficiently long enough to provide overlap within the reinforcement layers.

Foldable Solid RF Reflector Architectures

NASA's foldable large-scale parabolic reflector technology introduces two innovative architectures:

Concentric Stack and Connect (shown on the right): This design uses a stack of lightweight rigid panels (e.g., hexagons) made of a carbon composite sandwich construction that are arranged concentrically, resulting in a compact stowed design. Each panel is deployed from the stack one at a time by activating pairs of tubular composite hinges, and a second mechanism closes the gap between the deployed panels to create a seamless reflective surface.

Umbrella (shown below): Employing a set of thin-shell composite gores suspended from stiff backbone ribs, this design allows the entire paraboloid to be folded and unfolded like an umbrella. A novel apparatus consisting of a set of mechanically actuated push and pull rods enables the controlled and synchronized stowage of the multiple flexible connected gores each forming a serpentine shape with one or more lobes. Structural deformable composite elements are incorporated around the perimeter and between the gores to increase the deployed stiffness of the overall reflector and enable the synchronized gore deployment.

Both architectures use shape memory composite elements that are initially folded during transportation. Upon reaching the destination, the shape memory composite is heated, triggering the shape memory effect and causing the actuators to extend slowly, unfolding the reflector to its desired shape. The lightweight deformable composite materials in the parabolic reflectors enable the compact stowage, reducing mass and volume needs during transport. Additionally, precise control over the deployment process ensures accurate shaping and alignment, enhancing overall system performance.

Continuous Fiber Composite for Use in Gears

Designers are constantly seeking to improve the power-to-weight ratio of components in rotorcraft and other flight vehicles. One approach has involved using lightweight carbon fiber composite materials to replace gear web portions and other components that are typically made from steel. The problem with using fiber composite materials comes when more complex shapes are required. To create thickness variation and other accommodations for complex shapes, manufacturers can stack cut continuous fiber plies and/or form short, fiber-reinforced composite material to the desired shape. Unfortunately, these methods leave cut fiber ends within the structure, which often become initial sites for high cycle fatigue damage in high speed, high power density applications. Glenn's new method tackles this problem with one of three approaches. The first approach is applicable to gears that are planar in shape and have a single hub and a single rim. The hub and web sections of the gear are made as an integrated structure with decreased thickness from the hub inner diameter to the web outer diameter. The thickness variation is accomplished using multiple layers of continuous fiber composite material formed to specific shapes and separated by filler materials. The second approach is applicable to gears that have an extended gear body in the axial direction rather than a simple planar structure. In this approach, the gear body is made using multiple layers of continuous fiber composite material in the shape of a solid of revolution. The third approach is a power transfer assembly made by combining approaches one and two. With any of these three approaches, the material can be tailored to the structure by the properties of fibers used, the number of fiber layers used, and the location of the fibers relative to the neutral axis of the structure. Glenn's innovation opens the door for carbon fiber composite materials to be used for many applications for which they were previously unsuited.

Atomic Number (Z)-Grade Radiation Shields from Fiber Metal Laminates

This technology is a flexible, lighter weight radiation shield made from hybrid carbon/metal fabric and based on the Z-grading method of layering metal materials of differing atomic numbers to provide radiation protection for protons, electrons, and x-rays. To create this material, a high density metal is plasma spray-coated to carbon fiber. Another metal with less density is then plasma spray-coated, followed by another, and so on, until the material with the appropriate shielding properties is formed. Resins can be added to the material to provide structural adhesion, reducing the need for mechanical bonding. This material is amenable to molding and could be used to build custom radiation shielding to protect cabling and electronics in situations where traditional metal shielding is difficult to place.