Interim, In Situ Additive Manufacturing Inspection

manufacturing

Interim, In Situ Additive Manufacturing Inspection (MFS-TOPS-70)

Image-based method for real-time property inspection of printed parts

Overview

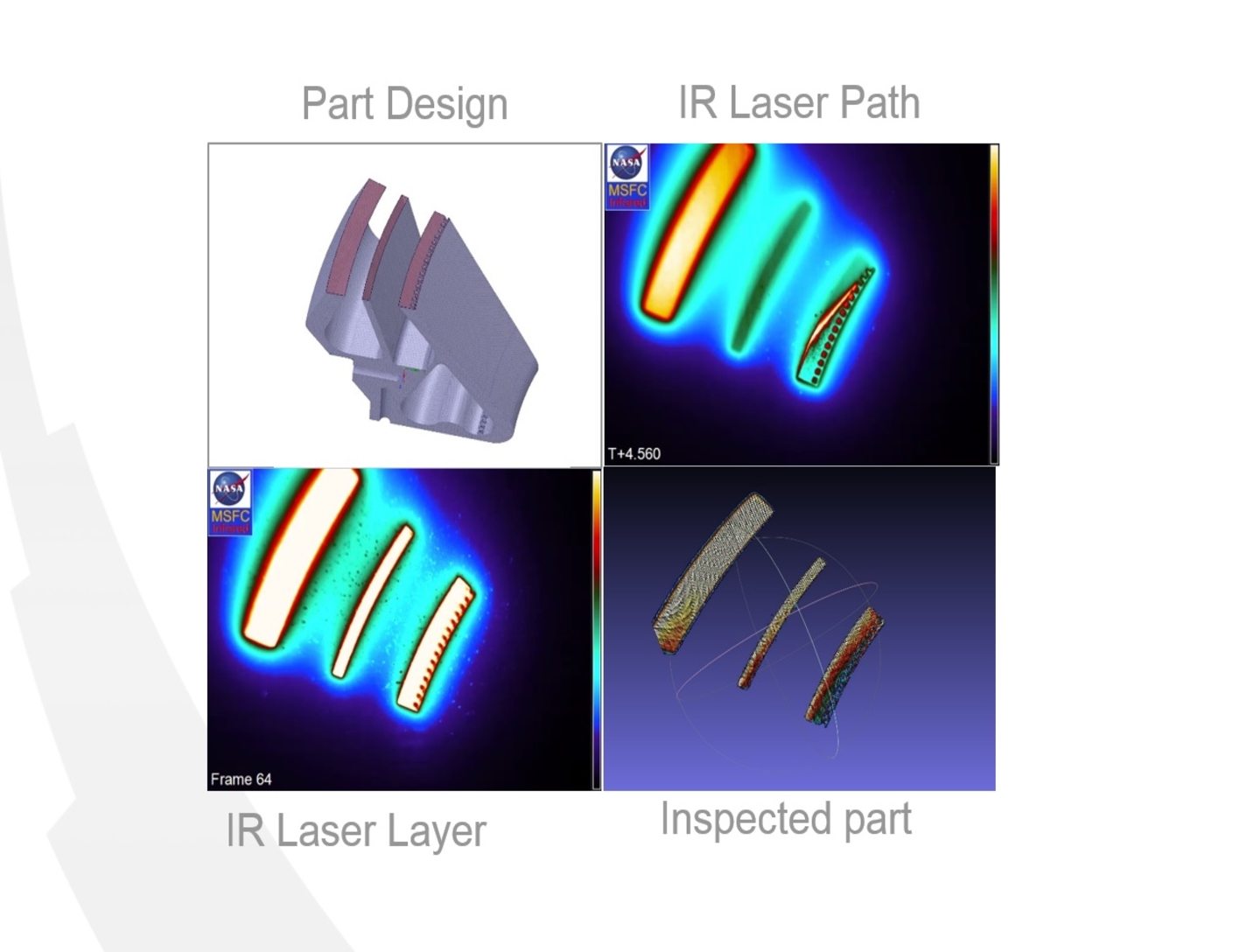

Researchers at NASA Marshall Space Flight Center have developed a novel method for interim, in situ dimensional inspection of additively manufactured parts. Additive manufacturing processes currently have limited monitoring capabilities, offering users little to no options in mitigating the high levels of product and process failures. This technology uses both infrared (IR) and visual cameras that allow users to monitor the build in real-time and correct the process as needed to reduce the time and material wasted in parts that will not meet quality specifications. The technology is especially useful for the in-process inspection of a parts internal features (e.g., fluid channels and passages), which cannot be easily inspected once the print is complete. The technology has the potential to enable the implementation of a closed-loop feedback system, allowing systems for automatic real-time corrections.

The Technology

The in situ inspection technology for additive manufacturing combines different types of cameras strategically placed around the part to monitor its properties during construction. The IR cameras collect accurate temperature data to validate thermal math models, while the visual cameras obtain highly detailed data at the exact location of the laser to build accurate, as-built geometric models. Furthermore, certain adopted techniques (e.g., single to grouped pixels comparison to avoid bad/biased pixels) reduce false positive readings.

NASA has developed and tested prototypes in both laser-sintered plastic and metal processes. The technology detected errors due to stray powder sparking and material layer lifts. Furthermore, the technology has the potential to detect anomalies in the property profile that are caused by errors due to stress, power density issues, incomplete melting, voids, incomplete fill, and layer lift-up. Three-dimensional models of the printed parts were reconstructed using only the collected data, which demonstrates the success and potential of the technology to provide a deeper understanding of the laser-metal interactions. By monitoring the print, layer by layer, in real-time, users can pause the process and make corrections to the build as needed, reducing material, energy, and time wasted in nonconforming parts.

.jpg)

Benefits

- Robust: leverages processing techniques to reduce false positive readings

- Flexible: can be implemented in existing systems

- Cost-saving: reduces time, energy, and material wasted in nonconforming parts

- Accurate: uses both IR and visual cameras for thermal and spatial accuracy

Applications

- Aerospace: complex injectors, internal coolant passage components, heat exchangers

- Automotive: exhaust system components

- Medical: orthopedic implants

|

Tags:

|

Similar Results

In-situ Characterization and Inspection of Additive Manufacturing Deposits using Transient Infrared Thermography

Additive manufacturing or 3-D printing is a rapidly growing field where solid, objects can be produced layer by layer. This technology will have a significant impact in many areas including industrial manufacturing, medical, architecture, aerospace, and automotive. The advantages of additive manufacturing are reduction in material costs due to near net shape part builds, minimal machining required, computer assisted builds for rapid prototyping, and mass production capability. Traditional thermal nondestructive evaluation (NDE) techniques typically use a stationary heat source such as flash or quartz lamp heating to induce a temperature rise. The defects such as cracks, delamination damage, or voids block the heat flow and therefore cause a change in the transient heat flow response. There are drawbacks to these methods.

Additive Manufacturing Model-based Process Metrics (AM-PM)

Modeling additive manufacturing processes can be difficult due to the scale difference between the active processing point (e.g., a sub-millimeter melt pool) and the part itself. Typically, the tools used to model these processes are either too computationally intensive (due to high physical fidelity or inefficient computations) or are focused solely on either the microscale (e.g., microstructure) or macroscale (e.g., cracks). These pitfalls make the tools unsuitable for fast and efficient evaluations of additive manufacturing build files and parts.

Failures in parts made by laser powder bed fusion (L-PBF) often come when there is a lack of fusion or overheating of the metal powder that causes areas of high porosity. AM-PM uses a point field-based method to model L-PBF process conditions from either the build instructions (pre-build) or in situ measurements (during the build). The AM-PM modeling technique has been tested in several builds including a Ti-6Al-4V test article that was divided into 16 parts, each with different build conditions. With AM-PM, calculations are performed faster than similar methods and the technique can be generalized to other additive manufacturing processes.

The AM-PM method is at technology readiness level (TRL) 6 (system/subsystem model or prototype demonstration in a relevant environment) and is available for patent licensing.

Optimization of X-Ray CT Measurement Accuracy for Metal AM Components

This NASA innovation is a method for quantifying and improving accuracy of X-Ray CT-based metal AM part inspection by comparing X-Ray CT data with a high-fidelity 2D surface imaging technique such as surface profilometry. Using surface profilometry that has a NIST-traceable calibration, the technique guarantees a specific level of high fidelity, allowing surface profilometry data to serve as a ground truth reference with which to judge X-Ray CT accuracy and detectability.

To deploy the method, both 3D X-Ray CT data and 2D high-fidelity surface images are acquired on the same metal AM part. 3D X-Ray CT data is then segmented and reoriented to extract a 2D X-Ray CT surface image. Measurements of features (e.g., surface-breaking porosity) are then made in both datasets, followed by a comparison of various metrics. This comparison serves two purposes: (a) quantifying the accuracy of the X-Ray CT inspection performed, and (b) providing an objective function which can be minimized to optimize X-Ray CT inspection. The objective function allows engineers to tune X-Ray CT parameters to minimize the function. These optimized parameters can then be implemented to achieve higher accuracy and defect detection reliability in X-Ray CT imaging. Once an X-Ray CT process is optimized for a specific metal AM component, analysis and certification can be accelerated.

This technology helps develop X-Ray CT-based metal AM part inspection processes with high accuracy and reliable detectability. Industries for which metal AM parts are desirable and safety, reliability, and fatigue life is of concern (e.g., aerospace, commercial space, automotive, medical) could benefit from the invention. Companies including X-Ray CT inspection system manufacturers using optical sensors and software, NDE data analysis software providers, and end-users in the industries may be interested in licensing this NASA invention.

Fully Automated High-Throughput Additive Manufacturing

The technology is a method to increase automation of Additive Manufacturing (AM) through augmentation of the Fused Filament Fabrication (FFF) process. It can significantly increase the speed of 3D printing by automating the removal of printed components from the build platform without the need for additional hardware, which increases printing throughput. The method can also be leveraged to perform automated object testing and characterization. The method includes embedding into the manufacturing instructions methods to fabricate directly onto the build platform an actuator tool, such as a linear spring. The deposition head can be leveraged as a robotic manipulator of the actuator tool to bend, cock, and release the linear spring to strike the target manufactured object and move it off the build platform of the machine they were manufactured on. The ability for an object to 'fly off of the machine that made it' essentially enables automated clearing of the processed build volume. The technology can also be used for testing the AM machine or the feedstock material by successively fabricating prototypes of the manufactured object, and taking measurements from sensors as the actuator strikes the prototype. This provides automated testing for quality control, machine calibration, material origins, and counterfeit detection.

Guided wave-based system for cure monitoring of composites using piezoelectric discs and fiber Bragg gratings (FBGs)

This system connects the properties of the guided waves to the phase changes of a composite part. The system measures temperature, strain, and guided waves during cure almost simultaneously. During life-cycle monitoring, it is feasible to use embedded fiber optic sensors for both load monitoring because of the ability to measure strain and damage detection because of the ability to record ultrasonic guided waves. The guided wave system is incorporated directly into standard curing equipment and technique. It has also been tested and works with flat panels as well as complex structures. The technology would be valuable to manufacturers of aircraft parts (fuselage, wing and other sections), marine hull sections, high speed rail sections, automotive parts and perhaps even building parts. One major application that exists presently, is the fabrication of fuselage and wing sections for aircraft where carbon fiber composite sections are used such as Boeing's 787 Dreamliner.